On Language Learning

23rd of July, 2025

It is endlessly fascinating to hear people recount how they are accomplishing something impressive. I'd even describe it as my favourite genre of nonfiction. You and Your Research is the pinnacle, but even some guy telling you how to bench three plates inevitably taps into the same magic. That special something is not about from replicating what the narrator did; we're not talking about tutorials. It's more about how it feels to get good. These stories are about the phenomenology of being correct. For me, currently, that story is learning Japanese. Specifically, my goal was to be better than the median native speaker in comprehension, writing and speaking. While that's not very impressive in itself (by definition, about 50 million people will fit the bill), it does mirror other skill aquisition. The story below is about how to put many hours into one thing, consistently.

Immersion learning is the practice of hearing and reading a target language, like, a lot. No need for grammar lessons, for textbooks, for apps; in the limit you can even drop dedicated study of vocabulary. Crucially, no speaking and writing! A pure form of this in the pre-internet era was J. Marvin Brown's Thai adult language school, where the students were forbidden from outputting the target language for as much as a year of full-time classes, just listening to two teachers interacting. The results had high variance, but reportedly some bona fide native-like speakers came out of this school. Today, for some languages, we have a very engaging media landscape as a substitute for the poor souls doing skits.

Equipped with this wisdom, I dutifully started watching the reality TV show Terrace House in Japanese, as so many others do who read too much on the internet. After perhaps a few days of dabbling and learning the syllabaries, I had found immense determination out of basically nowhere, and began immersion learning for many hours a day. At the same time, I felt as I was going insane, because it is rather frustrating to not understand a single thing of the thing you are listening to. Every word pouring into my ears was a reminder that I was going to spend a truly unreasonable amount of time to reach my goal, and I felt like this couldn't possibly work. While I intellectually believed that Chomsky's language aquisition machine was quietly working away at decoding the signal, viscerally I felt like a complete clown. To illustrate how it looked from the outside: I wore headphones and walked in a small circles on the carpet, listening to podcasts I didn't understand anything of, for hours at a time. Because immersion doesn't teach reading, I also studied 25 new kanji character meanings every day, alongside 20 vocabulary items, using spaced repetition.

Thus began a long, masochistic grind, something which I can definitely recommend. I'd want to suggest something else than language learning, but there's a reason this stuff is in every novel, the Bible, et cetera. Over time, I began to feel a sense of camaraderie with others who had done the pilgrimage in the past. James W. Heisig for instance, whose 1977 book Remembering the Kanji I used to construct mnemonics. Or, naturally, those who made blogs and videos just like what you're reading now.

After three months, I knew the meaning of all high school-grade kanji. That meant I could jump into reading, which I happily started with easier input like NHK Easy News. As for listening, I came to deplete the region-locked catalogue of my streaming service and moved to Let's Plays. It turns out that these are the absolute ideal medium for language learning. They have spoken and written language, both coupled and uncoupled, they provide visual context so you can watch comfortably at all levels, they contain different language registers, and for Japanese in particular they can even teach cultural context. I converged on one particular Let's Player with a standard Tōkyō pronunciation and about my demographics, which is useful for getting accustomed to an appropriate manner of speaking. If I was a linguist, out of all the unsubstantiated claims in this article, I would most like to empirically test the efficacy of Let's Plays for language learning.

After one year total, it was time to start reading real books. Here, in my dumbest stunt, I for some reason decided to read a Japanese translation of The Ego and Its Own, a 1844 treatise by Young Hegelian philosopher Max Stirner, most famous for being dunked on by Nietzsche. While the choice of the actual content also speaks volumes, it is needless to say that the appeal of this project was again the immense pain, in this case of making any sense of a text which would give me headaches even in my native language. I bought the book used online, and because it was already many decades old, the pages were brownish yellow and smelled of basement. It is amazing that anyone bothered to stock it in the first place. Through a line-by-line translation, I somehow made it through.

After one year total, it was time to start reading real books. Here, in my dumbest stunt, I for some reason decided to read a Japanese translation of The Ego and Its Own, a 1844 treatise by Young Hegelian philosopher Max Stirner, most famous for being dunked on by Nietzsche. While the choice of the actual content also speaks volumes, it is needless to say that the appeal of this project was again the immense pain, in this case of making any sense of a text which would give me headaches even in my native language. I bought the book used online, and because it was already many decades old, the pages were brownish yellow and smelled of basement. It is amazing that anyone bothered to stock it in the first place. Through a line-by-line translation, I somehow made it through.

There was a small, local Japanese language school offering classes and tutoring. I got curious and booked a trial lesson, where a basic assessment was to take place. I was quite excited at the prospect of a conversation partner, because I had not spoken to anybody before, besides of course myself. To my shock, my pronunciation was better than the teacher's, who had studied for 20 years. My grammar was presumably a bit worse, and I couldn't write nearly as well, but we both parted confident that I was doing something right, and that this school had nothing to teach me.

I began feeling comfortable enough with comprehension that I set my eyes on the JLPT N1, the highest level of Japan's official language tests for foreigners. This was not entirely for vanity, but because a university exchange program for taking math classes in Japanese required it. Sadly the next exam slot was fully booked, which however allowed me to chill a little by incorporating more handwriting, which the JLPT does not test. Some consider handwriting to be obsolete, because many native speakers aren't that great at it either and simply type everything, but in practice most people will be able to write more than 1000 characters. After 2 years total, I passed in the JLPT N1. I felt a little resentful at the fact that some had been quicker, with a few of people on the internet reporting 1.5 years.

Another very unwise idea formed in my tortured mind, namely that I should also pass some language test for natives. The choice fell upon the Kanji-kentei, a writing exam offering levels from 1st grade of primary school (10-kyū) to the end of high school (jun-2-kyū and 2-kyū, often taken before applying for a job), to college student with too much time (jun-1-kyū), to actual maniac (1-kyū). Naturally I decided on the highest level which can be taken outside Japan, the 2-kyū. By now I had done so many dumb things that a couple hundred hours weren't so bad, in fact it was rather meditative writing down all those characters over and over again. Ironically, this particular test did not even help in writing normal prose, because the whole point is to impart the uncommon characters that the average person wouldn't know. One part was very fun though. One of the categories of arbitrary things were yojijukugo, four-character idiomatic compounds. I have a real love for these. For instance 汗牛充棟, literally "sweat-cow-full-tower", means "a lot of books", as in "you have so many books that your ox starts sweating when you load the books onto it and the whole house is filled to the brim with them". I passed the kanken 2-kyū at 2.5 years of study total.

By this time, I was often thinking in the target language, especially after listening to something. Emotional matters, I find, are nicer to express in Japanese, because there is less need for constructing a full sentence with subject, verb, object, word order, casus, genus, numerus, prepositions. In English, just saying "scared" when you're scared is not only ungrammatical, but considered deeply silly. In Japanese, however, that's exactly what you do. Sad and disappointed: 「やれやれ。」Happy and excited: 「わーい。」Angry at the printer drivers: 「いい加減にしねえと今度こそぶっ壊すぞポンコツが!おっっっっら!!!!」

It was time to go to Japan; thanks to a very kind professor at Tōhoku University, I had been accepted into the exchange. From the outside, this would have seemed like the big goal, but I thought of it differently. It was in a sense just a tool to practice the language, which evidently I was not doing out of any practical reason. After stepping into a machine to Narita, my first flight ever, this perspective quickly changed. I had only spoken the target language for about an hour at that point, which paled in comparison to some 3000 hours of input. This is a very unique state to be in, the mental equivalent of iron oxide and aluminium powder waiting to be ignited into a violent thermal reaction. Toddlers must experience a similar sensation when they speak for the first time. Their surprise over the newfound power often shows on their little faces, and it's moving to observe. Yes, you can experience it as an adult, too, for the all-time-low price of one year's worth of waking hours.

Alas, the girl next to me in the plane and I started chatting. Wow! It was like that scene in superhero movies where someone looks down at their own grasping hands in awe after discovering, say, the spider powers. I could immediately express everything I wanted, and we had no trouble at all understanding each other. That little weirdo walking on the carpet in circles was proven right, showed them all, and was now stepping into a country full of people to talk to.

A veritable torrent of positive affirmations streamed my way. On good days, some people would ask if I'm half-Japanese, or, perhaps the highest praise, let themselves be convinced to reply in fast, natural Japanese by a perfectly executed greeting. I had no trouble understanding my complex analysis and quantum physics class. Other exchange students' respect was immediately secured. Complete strangers of all genders regularly told me I was handsome, which I'm not really sure how to interpret even now. It might have helped that I radiated a true and honest joy of being were I was at all hours of the day.

Of course, I still sucked at the language. Let's take my pitch accent. In English, if I incorrectly place the stress in "fireworks" on the second syllable, it sounds weird and you'd have to think a second to understand I didn't say "fire works". Similarly if the pitch accent is wrong in Japanese, people still understand, but it sounds awkward. Mine was still all over the place, even though I had tried to study it by looking it up for various words I was hearing. I had even published a browser extension for doing so. In general, my competence was rather jagged compared to a native, because I lacked exposure to diverse real world contexts. I was bad at reading names, clear articulation, onomatopoeia, polite language, skimming long text quickly, understanding Kansai dialect — the list goes on. This put me in funny situations now and then, like one time where I worked a 15 hour shift as a cashier at a local card game tournament, after frantically questioning my colleagues how to appropriately interface with our customers.「またのご来店をお待ちしております!」My ego was thus kept in check somewhat.

There were also times where my abilities generalized surprisingly well, for example when visiting a Rakugo (traditional storytelling comedy) performance done in Tōhoku dialect. In Rakugo, impromptu jokes with the audience are not unusual, so in the small chamber I became an obvious target. Luckily I had enough wits with me to come up with a good counter. Fun!

I started practicing tea ceremony and pottery at the university clubs, where I met many great people, from whom I learned a lot about our world. Particularly in the pottery club, folks are the complete opposite of some stereotypes floating around; certainly the warmest, most unconceited and curious people who I have had the pleasure to meet. I wasn't really equipped to build deep lifelong friendships, but did so anyway in at least one unlikely case, with the owner of the best jazz bar in Sapporo and widow to a certain legendary pianist. If you're reading this, Yasuko, hi!

Upon returning home, I went down to a diet of maybe 45 minutes of light entertainment per day, just enough to maintain my level. This is my current state. Interestingly, I lose way less vocabulary than I expected, and pronunciation seems to be improving. Fluency and output quality are somewhat poor; it turns out that the highest level one can accomplish is not to think in a language, but to not think in it any more. I still have to spend subconscious effort to speak well, meaning that my fluency degrades substantially when I'm surprised, embarrassed, or similar. Absent that, I might be able to fool someone into thinking I'm native, but only for a few moments. Worse yet, if you look at my history of words looked up in the dictionary, you would find such simple terms as 黄身 (egg yolk), 柄 (handle), 待ち受け (here, digital wallpaper). That means that, after 5000 hours of practice over 6 years, I have not reached my goal of native proficiency at all.

Luckily, it also means that my study is not yet over. I continue, and consider the practice a metaphor for other areas in life, where success comes less readily.

Appendix

A list of books and resources used during the learning process.

Literature

-

三四郎 — Sanshirō — Sōseki Natsume

Legendary for a reason. ★★★★★ -

坊っちゃん — Bocchan — Sōseki Natsume

Classic literature is supposed to be serious, but this one is so endearing and funny. ★★★★★ -

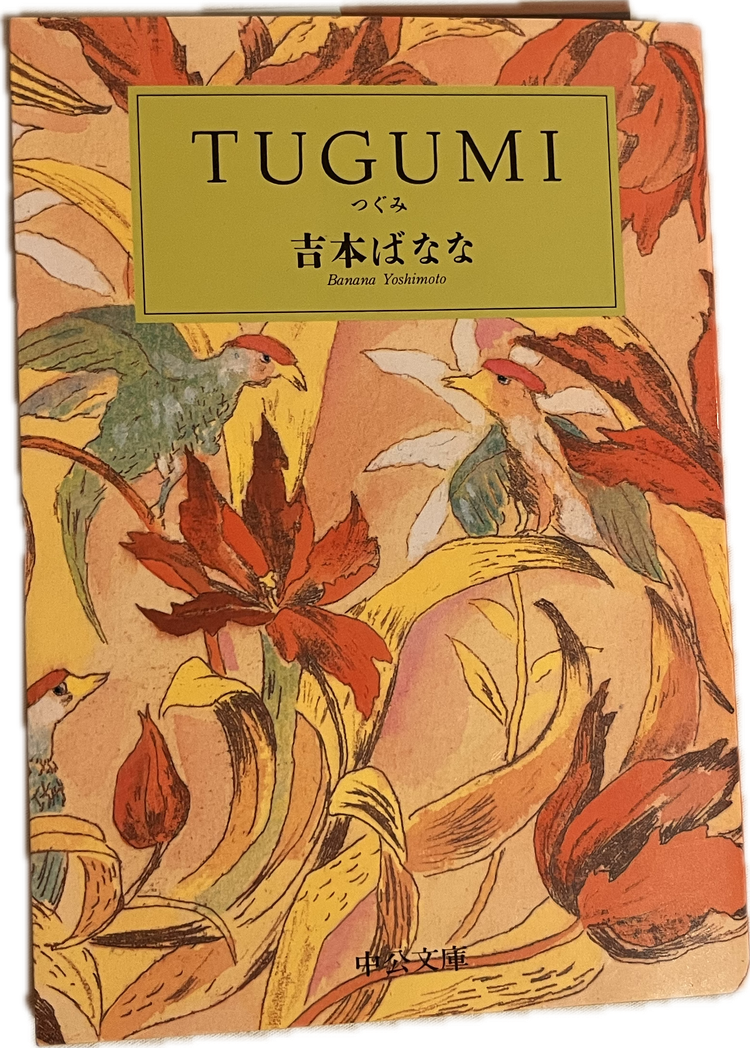

つぐみ — TUGUMI — Banana Yoshimoto

Mellow and tender. Recommended. ★★★★☆ -

雪国 — Snow Country — Yasunari Kawabata

Depression in book form, except that's a good thing. ★★★★☆ -

船を編む — To Make a Boat — Shion Miura

Nerding out about dictionaries, in novel form. ★★★★★ -

キッチン — Kitchen — Banana Yoshimoto

Melancholic, I preferred Yoshimoto's other books. ★★★☆☆ -

未来のミライ — Mirai of the Future — Mamoru Hosoda

Don't choose a book by its cover. ★☆☆☆☆ -

コーヒーが冷めないうちに — Before the Coffee Gets Cold — Toshikazu Kawaguchi

Lighthearted fun. ★★★★☆ -

走れメロス — Run, Melos! (and other short stories) — Osamu Dazai

The story is good, I don't get the writing style. ★★★☆☆

Resources

- Tae Kim's Guide - The most straightforward source for grammar. ★★★★★

- NHK easy news - Classic. ★★★★☆

- Remembering the Kanji - It's alright. ★★★☆☆

- Japanese Quest - Learn vocab with video game streams. Fun for beginners, watch sparingly. ★★★☆☆

- JapanesePod101 - The kana videos are great, but you need to stop watching after those. ★★☆☆☆

- Yomitan (Yomichan, Rikaikun) - This is what software is for. Install immediately. Great gains ahead. Switch to JP<->JP dictionary as quickly as possible. ★★★★★

- WaniKani - Did the trial chapters, too opinionated and not recommended over Anki, but the company is nice. ★★☆☆☆

- Anki - Study in style. ★★★★☆

- Kanji Koohii - A spaced repetition site for Remembering the Kanji. Thank you Fabrice, this is really good software. Some people sharing mnemonics there have bad taste. ★★★★☆

- Duolingo - bad. ★☆☆☆☆

- Shirabe Jisho - Clearly the best dictionary UI on the planet. ★★★★★

- JMdict (upstream of jisho.org) - From my one interaction with Jim he's really nice, so it makes sense he gifted us this amazing dictionary. ★★★★★

- Jisho Pitcher - Adds pitch accent to jisho.org. By yours truly. Score withheld because of conflict of interest.

- Nihongo no Mori - I don't understand why this is free. Yuka single-handedly made N1 happen for me. You need to find a way to give them money. ★★★★★

- Wadoku - DE <-> JP dictionary. Try it if you speak German, it's very good. It even has a pitch accent dataset. Thank you Dr. Latka! ★★★★★

- Local language tandem - You take turns speaking your target and native language. Fun if you're ready to speak, but the real benefit is social, not pedagogical. ★★★☆☆

- Satori Reader - Quite engaging for beginners, try to get off it quickly. ★★★☆☆

- Dogen's Pitch Accent videos - It's either this or NHK's accent dictionary. But as said there's a ceiling to conscious knowledge about pitch accent. ★★★★☆

- 漢字検定WEB問題集 - Fun, free, reasonably effective for the Kanken. ★★★★☆

- 史上最強の漢検マスター2級問題集 - the title might be right, I think it's the best Kanken book out there. ★★★★★

- The official Kanji-Kentei Nintendo DS game - This is pure gold. ★★★★★